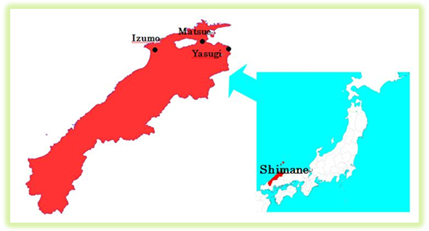

The Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), Japan’s oldest chronicle, was compiled 1,300 years ago in 712. About one-third of the Kojiki is concerned with the world of mythology, beginning with the birth of Japan, and many of the myths involve Shimane Prefecture.

In commemoration of the 1,300th anniversary of the compilation of the Kojiki, the Japan Myth Expo in Shimane will be held in Shimane Prefecture for 114 days from July 21, 2012. IHCSA Cafe visited the tourist spots of Izumo Grand Shrine and its vicinity, where the main expo venues will be, as well as Yasugi City and Matsue City, to explore their attractions.

|

|

![]()

![]()

Where the Gods Gather

Izumo Grand Shrine is the symbol of the Izumo region, the so-called land of the gods. The shrine’s principal deity is Okuninushi no Mikoto. According to myths written in the Kojiki and elsewhere, Okuninushi, who had been engaged in building the land of Japan, presented the country to gods who had descended from heaven, and Izumo Grand Shrine was then constructed as a reward to Okuninushi. In this myth about the handing over of the country, it is said that Amaterasu Omikami, the principal deity of Shinto and regarded as the progenitor of the Japanese imperial line, dispatched one of her children as an envoy in the negotiations with Okuninushi. Subsequently the descendants of that child served as the chief priests of Izumo Grand Shrine; the current chief priest is said to be the 84th generation in that genealogical line.

In scenery that seems to symbolize the formation of Japanese culture centered on rice cultivation, the road running from Izumo Airport in the direction of Izumo Grand Shrine is endlessly lined with paddy fields. Gazing at this archetypal image of Japan, I felt as if my soul, so fatigued by city life, was being soothed.

|

|

|

The imposing Seidamari-no-Torii gate |

At the entrance to the approach to Izumo Grand Shrine, there is a towering wooden torii gateway. (This entrance is called the Seidamari, which means the “place where vigorous powers gather,” because in the past it was always crowded with stages and show tents and thronging with people.) From the torii the approach, lined with pine trees and paved with stones, unusually goes downhill. On the way down, on the right there is a small shrine, called the Harai no Yashiro, where visitors can exorcize the evil spirits that have imperceptibly gathered inside them. After purifying my body and soul here, I carried on along the approach.

|

|

|

Harai no Yashiro |

|

|

|

Okuninushi gazes gently at the rabbit. |

At last, beyond an unusual iron torii and rows of pine trees, a shrine building came into view. After the pine trees have ended, there is a place for visitors to wash their hands and rinse their mouths before going on to worship. On the left here there is a bronze statue relating to the myth about the white rabbit of Inaba, which shows Okuninushi’s deep compassion. (The story goes that a white rabbit was ill-treated by Okuninushi’s mischievous brothers but then saved by Okuninushi, who was rewarded by being able to marry a beautiful goddess.) On the right there is a statue of Okuninushi receiving the power of marriage-making (in Shinto terminology, sakimitama and kushimitama) from a ball of light hurtling across the sea. Izumo Grand Shrine is especially popular among young women, who believe that their prayers here to meet the right partner will be heard.

|

|

|

The god of marriage-making |

|

|

Passing through the bronze torii at the entrance to the shrine’s precincts, I arrived at the outer shrine building, which is adorned by a magnificent large shimenawa (sacred straw festoon), and the main hall, currently hidden because it was being renovated. The main hall was constructed in 1744 and is a national treasure. It has been undergoing five-year renovation work since April 2008 and was scheduled to reemerge from behind the cover in early June of this year.

|

|

|

This spot is where three support pillars were unearthed. |

There are two things of interest in the vicinity of the main hall. The first is the spot where three giant pillars, thought to have supported the main hall in the past, were excavated in 2000. They are said to lend credence to the theory that in the Heian period (794-1185) the main hall reached a height of 48 meters, twice the size of the present structure.

|

|

|

Accommodation for countless gods |

The second is a long and narrow buildings called the Jukusha, situated to the east and west of the main hall. It is said that in October according to the old lunar calendar gods from around Japan would gather at Izumo Grand Shrine and hold a meeting to decide various things relating to human life, including marriage. At such times, the gods from around the country would lodge in the Jukusha. Once a year the gods would leave their own districts and congregate at Izumo Grand Shrine. This is the reason why, in the old calendar, the month of October was called kannazuki (month without gods) by people around the country---except for folk in Shimane Prefecture, who referred to it as kamiarizuki (month with gods). Even today, Shimane Prefecture is the only place where the gods congregate.

|

|

|

These giant pillars were excavated in front of the main hall. |

Solving the Riddles

There are two exhibits at the Shimane Museum of Ancient Izumo, located close to Izumo Grand Shrine, that especially stir romanticism for the past.

The first exhibit features the huge wooden pillars that were excavated in front of the main hall of Izumo Grand Shrine in 2000 and are thought to have been used in the construction of the main hall in the early Kamakura period (1185-1333). Until 2000 it had been widely argued that construction of a huge structure rising to a height of 48 meters would have been impossible with the technology available at that time, but the discovery gave credence to the theory. If the 48-meter-high hall really did exist, it would have been taller than the Great Buddha hall at Todai-ji temple in Nara and the highest structure in Japan at that time.

|

|

|

Models show how the great hall might have looked. |

In the museum there are also models of how the colossal main hall might have looked in the past. There are various theories about the main hall’s shape, and the museum has several models reflecting them. In the Heian and Kamakura periods the main hall was twice the size of the present structure; there is even a theory that the ancient hall towered as high as 96 meters.

|

|

|

Many bronze swords were discovered. |

|

|

|

The bronze bells speak romantically of ancient times. |

The second exhibit radiating romanticism for ancient times is a display of 358 bronze swords, 16 bronze pikes, and 45 bronze bells excavated in the 1980s and 1990s; they are all designated national treasures. This excavation of bronze artifacts, one of the largest ever, is evidence that a group with enormous power existed in this region and suggests the possibility that this region was deeply involved in the formation of Japan.

Wonderful Paintings, Wonderful Gardens

Next, departing from the world of myths, I visited Adachi Museum of Art in the city of Yasugi. This museum houses the collection of about 1,500 paintings of the founder, Zenko Adachi (1899-1990), including many modern and contemporary nihonga (Japanese-style paintings). The exhibited works are seasonally changed. The paintings, centered on the works of Taikan Yokoyama (1868-1958), are indeed wonderful, but so also are the museum’s Japanese-style landscape gardens, built passionately by the founder himself in the belief that “a garden is also a work of art.” An American magazine about Japanese gardening has designated the gardens at the Adachi Museum of Art as the best in Japan for nine consecutive years since 2003. They are also introduced in the Michelin Green Guide, which gives them a three-star rating.

After entering the bright, modern front entrance, I followed the course, and immediately gardens came into view that made me feel as if I were in Kyoto. On the right side of the corridor there is a moss garden, and on the left side there is a quiet tea garden gracefully surrounding a tearoom. Already I felt as if I had entered another world. For a while I let the greenery of the moss and pine trees sooth my eyes.

|

|

|

The spacious dry landscape garden |

Feeling refreshed, I went on to the lobby, where the high glass walls ensure that your view is never obstructed. Outside there is a huge dry landscape garden. I had never seen such a spacious dry landscape garden before and for a while felt completely overwhelmed. I tried standing near the glass window, moving away from it, and sitting down, but for some reason I could not settle. The garden just makes you want to keep changing your position. The awe-inspiring feeling of spaciousness does not come just from the garden itself, either. The mountains in the background, centering on Mount Katsuyama, seem to blend wonderfully with the garden scenery. Apparently the owner of the museum has obtained promises from the people who own the surrounding mountains that not a single utility pole should be erected there.

|

|

|

The landscape gardens reproduce the world of Japanese-style painting. |

On the right Mount Kikaku, with its impressive yellowish rock face, looms behind the pine trees. The waterfall flowing down from this mountain was apparently built artificially so as to harmonize with the landscape garden. The founder endeavored to reproduce his beloved world of nihonga in the gardens, putting theory into practice as it were. The resulting delicacy and dynamism are truly awesome.

|

|

|

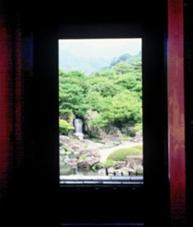

This cutout makes the garden look just like a hanging scroll. |

Farther along there is a place where visitors are almost automatically stopped in their tracks. It is a scene of the garden framed by a window. Be it a dry landscape garden or a white gravel and pine garden, a sliver cut out in the shape of a window frame or alcove radiates a completely different kind of elegance from that of the overall view. Quite unlike the beauty of the overall garden blending with nature, this scene has the beauty of a painting in which the silhouettes of the trees in the foreground create a special accent and perspective and more emphasis is given to light and shade.

In the innermost part of Adachi Museum of Art there are two more quite different gardens, which, unlike the other gardens, visitors go outside to admire. On the left side of the course there is a pond garden, where red and gold carp swim around happily in the abundant spring water. This garden is just as soothing as the dry landscape garden or the moss garden, but in a more moisturizing way. It makes you realize that like trees and greenery, water has a healing effect on the soul as well.

|

|

|

The pond garden lubricates the mind. |

Turning right along the course, there is a garden of stones and pine trees set out on white gravel. The white gravel accentuates the pine trees, and the superb arrangement of stones creates a shady atmosphere. It is said that this garden is a recreation of the world depicted in Yokoyama’s masterpiece Hakusa seisho (The Beautiful Pine Beach).

|

|

|

The white gravel and pine garden |

Finally, after enjoying the sense of liberation that comes with being outdoors and feeling even more the blessings of nature, I went up to the exhibition room on the second floor to enjoy the world of nihonga. The idea of guiding visitors through the gardens first and then into the world of nihonga is superb.

|

|

|

A pleasure boat plies the moat around Matsue Castle. |

The Castle Town of Matsue

The symbol of Matsue, without a doubt, is Matsue Castle. Built in the early seventeenth century by the feudal lord Horio Yoshiharu, the castle is now designated as an important cultural property of the state. Samurai residences remain in the vicinity of the castle, creating a castle-town atmosphere, and visitors can enjoy the scenery from one of the pleasure boats plying the castle moat as well.

|

|

I boarded one of these pleasure boats at a landing point near the site of the main gate of Matsue Castle. On the left you can see the castle walls and, as the boat moves along, Matsue History Museum comes into view on the right. Some young female tourists were cheerfully riding rented bicycles along the promenade around the castle, their black hair blowing in the wind. After the boat had passed Ugabashi bridge on the right and followed the castle wall to the left, a historic samurai residence came into view on the right. This is the Shiomi-Nawate district, which even today retains the atmosphere of the Edo period (1603-1868). Green pine trees peered over the brown wooden wall, and a white lantern hung on the large gate. Riding along in the boat, listening to the boatman’s eloquent talk about the history of Matsue Castle, and gazing at the castle walls on the left and the samurai residences on the right, I began to feel very relaxed indeed---at one with the fowl playing on the surface of the water.

|

|

|

Heads down, everyone! |

|

|

|

Matsue Castle looks especially grand when seen from the boat. |

One of the many enjoyable aspects of this pleasure boat ride is the boatman’s banter. Apparently it is a popular job that attracts many applicants not only from Shimane Prefecture but from across the country. I asked the boatman what the secret was for getting employed despite the many applicants. “The conditions are your looks,” he replied with a laugh, “and a good singing voice.” “So let me sing you a song,” he added, and, almost as if he had planned it, began singing a Shimane boat song just as we passed under a bridge. Excellent timing! The bridge produced a marvelous acoustic effect, and his melodic voice resonated wonderfully. The boatman’s performance drew a thunderous round of applause from the passengers on the boat.

Speaking of bridges, there is one ritual on the pleasure boat ride that I really must mention. Several of the bridges along the moat are very low, so every time the boat passes, the boatman has to lower the roof of the boat. As the roof lowers automatically, the passengers have to lower their heads too. Funnily enough, this ritual creates an odd sense of camaraderie among the passengers.

The leisurely boat ride takes just less than one hour and goes past places you would not otherwise have the chance to see. It’s definitely worth doing!

|

|

|

Mr. Futao Itami, a master of Japanese confectionery |

After the relaxing ride, I dropped in at the Matsue History Museum by the moat and had some Japanese confectionery and green tea at the Kiharu cafe, which is highly recommended by locals. Kiharu has a Japanese confectionery bar where Mr. Futao Itami, certified as the present master, demonstrates how to make creative Japanese confectionery and sells them.

|

|

|

Mr. Itami’s superb warabi-mochi |

The delicate and colorful confectionery at the counter all looked absolutely delightful. When I clearly could not decide which to choose, Mr. Itami confidently recommended me to try the warabi-mochi (made from bracken starch).

Sitting myself down in the tatami-floored corner reserved for eat-in visitors, I gazed out at the Japanese-style garden. Soon a smiling waitress brought over my tea and lush green warabi-mochi. When I took a bite of the jelly-like confection covered in soybean flour, I didn’t need to chew at all; it just dissolved instantly in my mouth. What a superb taste! At that moment, I understood exactly why Mr. Itami had been so confident. Glancing out of the window, I saw the castle donjon looking down on me.

The flow of time in Matsue was real quality!